Walls: A documentary of segregated schools

/In 1999 and 2000, I worked with two film students Matthew McLean and Dantia MacDonald to make an independent documentary about the struggle of Romani children for equal education in the Czech Republic. It was one of those hidden stories journalists search for--a significant but largely unknown injustice. At the time, 70 percent of Romani (sometimes called Gypsy) children in the Czech Republic were channeled into special schools for the mentally disabled. Before our documentary only a handful of articles had been written about the problem in the English press.

I was a young reporter working part time for The Prague Post and I was handed the thick government report on the special schools because no one else wanted to tackle it. But instead of feeling put upon, I saw in it one of the biggest stories of the decade. I spent the next several years writing about the Roma, often about the special schools. And I finished the documentary Walls.

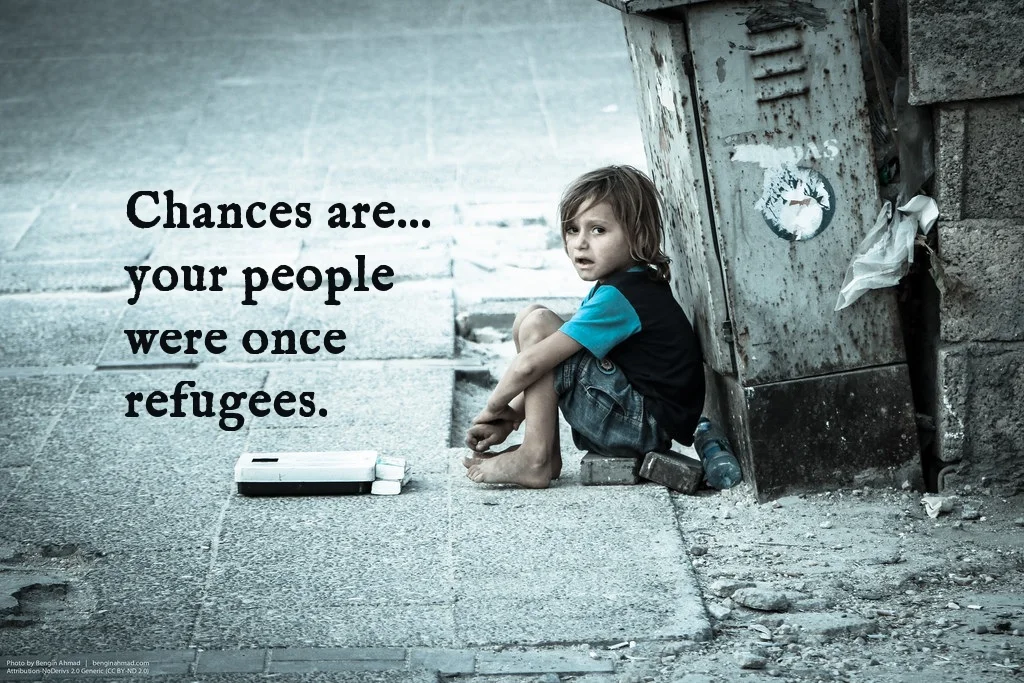

The film was the kind of documentary I'd always dreamed about--raw, a real-life story with "plot" and fiercely rebelious. Public trains provided our film crew transportation and the kitchen floors of ghetto homes gave us our base camps. The result is an incredible story following nine-year-old Karel and fifteen-year-olds Anezka and Pepino as they grapple with the segregated schools and their own growing understanding of their desperate chances in a deeply racist society.

It's been sixteen years now, enough time for another generation to grow up and pass through the schools. Today desegregation is still the hot issue it was then. The names of institutions have been changed to muddy the picture, but much of the problem remains the same as it was then.

The film remains relevant for all of those reasons, but the way I view it now is quite different. I am no longer a young, idealistic, foreign reporter. I have made this country my home. And I'm a parent of adopted Romani children. I too have been told to put my child in a special school. Now the line between journalist and everyday life has been blurred.